It was on 17 March 1858, and it happened in my hometown decades before I was born. The Consett Iron Works, which ceased operation in 1980, was located in the neighbourhood of Berryedge, Blackhill, and Consett. It employed thousands of Irish. Unfortunately, the English workers there and these Irish employees had perpetual mutual conflicts, manifesting in great hatred. Thus, began what has now taken its place in both British history and Irish history as “The Battle of the Blue Heaps.”

There were altercations here and there which caused serious consequences. They seemed to typically occur when paydays came around, approximately every two weeks, most likely because at least some of the pay was spent on imbibing of the alcohol kind. As reported, this likely resulted in brutal, drunken battles. But it was the one on that Saturday, 17 March 1858, on which unlawfully serious “shenanigans” took place during a drunken sojourn into British history which not only led to a suspension of business; a call to arms to the tune of 10,000 men; the deployment of the military; and indescribable chaos.

The Battle of the Blue Heaps apparently started at a so-called “public house,” also known as a pub and a residence, where drunken English and Irish turned that night into a memorable one, indeed, with the English winning by beating the Irish, literally.

On a fortnight after (Saturday, 31 March 1858), a party of drunken Irishmen came down a street only to meet up with Englishman John Sanderson,

An Iron Puddler At Work

an iron puddler at the Consett Ironworks. An iron puddler is an occupation involved with the process of converting pig iron into wrought iron. Without a thought to his skills or his importance as a co-worker, the group started in on Sanderson, ferociously attacking him by kicking him in his head and the rest of his body after rendering him helpless onto the ground marked by the blue heaps of iron residue from the Consett Iron Works. Facing life-threatening injuries, he survived but with permanent scars.

So where might there be a discussion (if there was to be one) about the attack? Well, a pub, of course; namely, Hewitt’s public house in Blackhill played host on Saturday, 17 April 1858. A group of both Irish and English convened. Not only were Irish eyes not smiling, so, too, was the case with the English.

After the typical abusive jawing prior to real trouble ensued here as well, the English drove the Irish out of the public-house with their physical aggressiveness. Sometime between eleven and twelve o’clock, according to news reports of the time, the police arrived and the fighting ceased.

On that next day, Sunday morning, 18 April 1858, all was quiet, with the locals expecting it would / might remain such until the next payday at least!

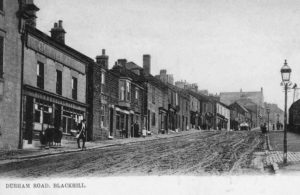

The Irish, however, had other ideas, despite the fact that it was the Sabbath. Toward evening they assembled at Berryedge and formed a mob estimated to be between five to six hundred. Outfitted with weapons of all kinds, including bludgeons and guns, they proceeded to Blackhill with a clear intent of attacking any English they encountered. While many kept out of the way, a few were determined to inflict pain on all the English that they encountered. Most of the English, however, avoided conflict although there were a few citizens who were badly beaten.

Because of the lack of resistance, the group took off to confront those in the house of a man named Joseph Curry, a proprietor of a pub, known as a “publican,” or a landlord. He had greatly annoyed the Irish as he would only allow Englishmen to be his customers, absolutely prohibiting the Irish to drink in his establishment.

Curry evidently saw the mob coming. As soon as the mob made its appearance, he locked, bolted and barricaded his doors. Although the Irish demanded to enter, the angry group was denied an open door and subsequently threatened to come in forcibly. They apparently wanted to see if there were any English patrons being hidden in the residence, and after receiving another firm “no,” all of the glass windows and their frames in the building were broken.

The publican landlord, in a vain attempt to stop the group, fired a gun with powder, apparently making them even angrier. This act tended to exasperate them all the more. While screaming epithets that went beyond simple cursing, the mob finally forced its entry and invaded every area of the building.

Anyone who was present in the residence, including Curry, had already evacuated it. Finding no humans to attack, the rioters commenced destroying everything in sight, be they items on tables; the tables themselves; drawer contents; chairs; and drinking items and crocks. In short, nothing was immune.

In addition, the tappers for the barrels containing alcohol were opened, not only allowing the revellers to drink as much as they wished but to waste the rest. It was estimated that 15 gallons each of brandy, rum, and gin were gone.

Finally, it was also estimated that they further took £47, 10s in money, along with anything else of value that they could take that survived the destruction.

Despite the seven policemen who reported to the pub, they were utterly powerless to effect anything against such an infuriated multitude. Finally, the Rev. Mr Kearney, a Catholic priest, finally arrived at the scene, exhorting the crowd to disperse.

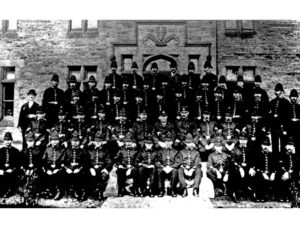

Still, the Irish group persevered and on Monday and Tuesday, 19-20 April 1858, at the site where the Shotley Bridge races used to take place, a group of Irish people gathered there (they called it No. 1). Once this became known to the headquarters of the Durham County Police via communication from a superintendent named Thompson, a large group of men, armed with cutlasses, were dispatched to Blackhill and Shotley Bridge.

On Wednesday, 21 April 1858, James Hoy, an Irishman, was taken into custody at approximately 1:30 a.m that day. Hoy, possessing a dagger and was believed to have been one of the Curry house destroyers. At half-past eight o’clock on the same morning, a Sergeant Marley and his police posse arrested Michael Kelly, another Irishman. He was found at the Daniel Branaghan pub in Blackhill. Kelly was armed with a loaded gun and resisted arrest violently, but he was disarmed and overcome. Kelly was subsequently charged as one of the heads of the party who destroyed the Curry pub, known as the “The Commercial Inn”.

The arrests of these two men resulted in 5,000-6,000 amassing at No. 1. Mostly everyone was armed. The English, calculating the likelihood of a disturbance, prepared for a conflagration, and in so doing, they were ready. They gathered by the thousands at Blackhill, ending up with a group of 3,000-4,000 people who were fairly heavily armed with daggers, guns, iron bars, bludgeons, and a myriad of sharp implements designed to cut.

They also had four small cannons.

Newcastle, a military stronghold, had been summoned by the magistrates to call up its red coat troops in an attempt to stop the Battle of the Blue Heaps.

Simultaneously, with the English setting up at No. 1, the Irish had assembled a show of great force at Berryedge, about half a mile distance away. As the English had started toward the village, R.S. Surtees, Esq., of Hamsterley Hall, and M. Kearney, Esq., of the Ford., both of Lanchester, and two of the county magistrates entreated the group to stop the journey to likely bloodshed in Berryedge. It was not easy, apparently, but they reached a consensus.

At some point, Shotley Grove’s Peter Annandale, Esq. arrived, and he also worked with the other magistrates to implore the men from attacking the Irish.

While the majority of the assembled English was apparently calm, some did not wish to listen to the entreaties of their magistrates, instead, chanting, “Berryedge,” “Berryedge,” wishing instead to attack the Irish in the town.

What they apparently wanted was to have the magistrates help the police in apprehending the men involved in the riot on the past Sunday night. The magistrates told them they believed that the military, which was apparently en route, would be adequate in restoring order and coping with what, hopefully, was not to come.

Just as the English contingent was on the point of returning to Blackhill, a cry was raised that the Irish had formed a Berryedge contingent and they were coming toward the English. The latter saw them coming and instantly jumped over a wall off of the road. They took up their former position at No. 1. In no time flat, the English had fortified their position with the four cannons, loaded up with old nails and slugs, and people in battle formation; namely, those with muskets in front and those with other implements of conflict behind.

Some of the English decided not to participate as things escalated, dropping their weapons and moving off into the distance. Still, in all, the English still had great power in its contingent.

At approximately the time of the defection, a body of 22 police, under the command of the aforementioned superintendent, Thompson, arrived. As they proceeded down the road towards Berryedge, they came within a hundred yards of the Irish.

When the Hibernians, an Irish Catholic fraternal organization, began to enter the No. 1, these individuals who were either born in Ireland or at least of Irish descent were entreated by a Mr Surtees who galloped towards them, to not move any further forward. But everyone was very agitated, and they told him they would rather die “in their own blood,” than not drive the English out of No. 1. According to reports, there were many women also in the group, speaking aggressively urging men to go on the attack.

The problem, of course, was what the English represented in equipment-power, they lacked in numbers in relation to the Irish contingent. Also, while actual firearms were not a big part of the Irish arsenal, they did have preferred items to them such as pokers, coal rakes, knives, hammers, and iron bars.

Interestingly enough, as bloodshed appeared unavoidable, Rev. Kearney came in from Berryedge, and the Irish were quieted. On the English side, apparently, Kearney and the rector, the Rev. B. Thompson, were attempting to stop hostilities on that side. The Catholic priest suggested to Surtees that he should use his influence with the English to work on their withdrawal from the field, with the former handling his side of things. Surtees complied.

It took some doing, but it appeared that most of the groups started to disperse.

Just then, the situation changed, with a melee coming from the Irish contingent consisting of hats flying and sticks and other implements thrown in the air. However, the magistrates again intervened as did the Catholic priest, causing the majority of the fighting men standing down, with the so-called “cannoneers” leaving the area last. It appears that the mediators had argued that the military would arrive and take action on whichever side started hostilities, which no one wanted, apparently.

Just as both groups gave in, and the policemen started to relax, sitting down at the side of the road, the Sherwood Foresters, under the command of a Lieutenant Colonel Mellish, (who sadly died in April 1864) came in their red coats from the direction of Shotley Bridge.

They had been at the Newcastle barracks, about to sit down to dinner, when they heard that their assistance would be required to aid civil authorities within a riot. Orders were issued for instant deployment, and transportation in the form of coaches, cabs, and other modalities was dispatched. Fully armed, the military headed out toward Shotley Bridge.

Upon arrival, the residents of the area were cheered as they marched in. Understandable, there was great consternation because the rioters could have come beyond any fighting to their doorsteps.

As they headed up toward Shotley Bridge, they were intercepted on the road by the magistrates coming from No. 1. Mellish and the magistrates had a brief conversation and Mellish then ordered the soldiers to “fix bayonets.”

As the regiment marched, they were joined by the police who assembled behind them, followed by thousands of people. The Irish and English had assembled into their own contingents in the area. As a show of force, the military group, having deployed into line, the men were marched across the Common and approached the wall where the Irish were behind a half an hour before.

Having made their point, the bayonets were taken down and off.The contingent was put to rest in a grassy area.

The Irish had, by this time, all retired into Berryedge. The armed English were dispersed into a group which joined the general throng of observers. The soldiers, through their show of force, encountered not one “enemy.”

After about three-quarters of an hour of remaining on the grounds, the soldiers headed back to Blackhill. They set up camp in a field behind Curry’s pub residence. They then dined on bread and cheese as well as a libation of ale. This being provided for them. Ultimately, fifty of the men remained in the village. The rest of the contingent, having done its job, went back in a short while to Shotley Bridge. They went to the vehicles in which they had travelled and headed back to Newcastle.

As one might imagine, in the evening, Curry’s property attracted a group of curious residents. It may have been a slight recompense for the publican that, casks replenished, people came to see the destruction. What they saw was likely quite astonishing. What with the broken windows, pieces of furniture cast about, and a greatly damaged exterior given the pelting with stones. The estimate of the damage including the money that was stolen came to approximately £200.

No doubt English (and some Irish) eyes smiled that night as neighbours walked around the streets in groups. Thankfulness for the restoration by many parties of peace and quiet had been returned to the village, my hometown. Reportedly one of the Sherwood Foresters was heard singing a beautiful song of great sentiment. To which an appreciative throng of townspeople listened.

The Battle of the Blue Heaps took its place in British History and Irish History.

Continued Below

The Ringleaders Day In Court

Author: Martin Boyle

Copyright © Martin Boyle 2018